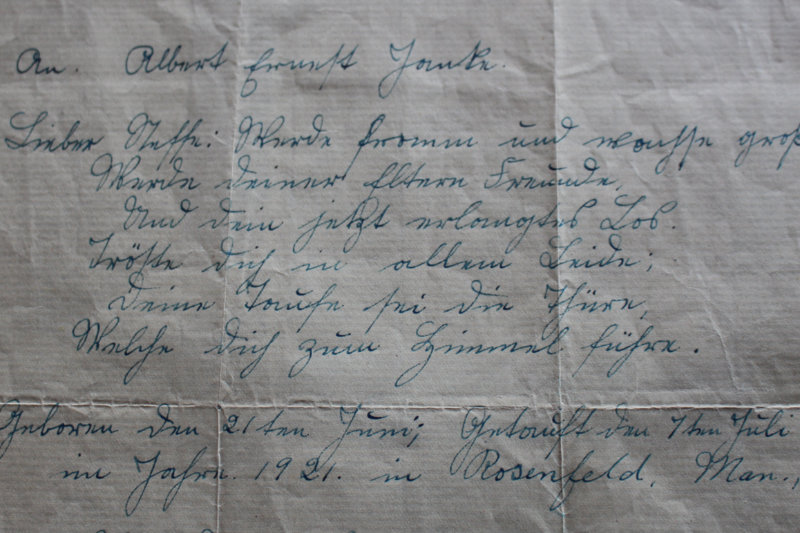

When my father was baptized as an infant in 1921, his godfather, who was his eighteen-year-old uncle, wrote him a letter. I still have that letter. The letter is in German. My father’s father and his uncle were born in Canada, but their parents and older siblings had been immigrants of German heritage. They’d been living in Russian Poland before they emigrated to Canada. When my father was in his seventies, my parents decided to have the letter translated. Both my parents spoke German as children. I suspect they would have remembered enough to translate the letter on their own if the letter hadn’t been written in old German script. My mother located someone who was able to read this script and had the letter translated into English.

When I researched old German script on the Internet, I discovered that two major styles of writing emerged in Europe: Gothic, which had been used since the 9th century, and Roman, also known as Antigua or Latin. Roman eventually became the standard throughout most of western Europe, Canada, and the United States. The Gothic style prevailed in the Czech Republic throughout the 1700s, in Scandinavia and the Baltic countries through the 19th century, and in Germany until 1941.

The old German handwriting known as Kurrentschrift evolved from Gothic cursive handwriting at the beginning of the 16th century and became normalized in schools in the 19th century. Characterized by sharp angles, it was apparently very hard to write. An updated version called Sütterlin Kurrent was developed in the early 20th century to give schoolchildren an easier start in writing. I compared my great-uncle’s letter with samples of the both styles of Kurrent handwriting I found online and determined it was written in Kurrentschrift.

In the early 20th century, a debate emerged with some calling for the use of Latin script to fall in line with the standards in the rest of Europe. The early years of Nazi rule promoted the Gothic script as part of “nationalism,” but in 1941 the regime reversed that stance and tried to ban the use of German fonts and scripts. This was driven in part by a need to publish its propaganda and have it understood in occupied countries. Kurrent was no longer taught in schools. After the war there was little enthusiasm for reviving the German script, which remained linked in the minds of many with extreme nationalist ideology. It was still used in some places and taught in some schools as an addition to Latin script, but gradually Latin (or Roman) script became the norm.

The cursive writing most widely used in Germany today is like that used in North America. However, the future of that current form of cursive writing is uncertain, at least in North America. Knowledge of cursive is declining. In the 21st century, it has been removed from or relegated to optional in many school curriculums, as block printing or use of the keyboard becomes more prominent.

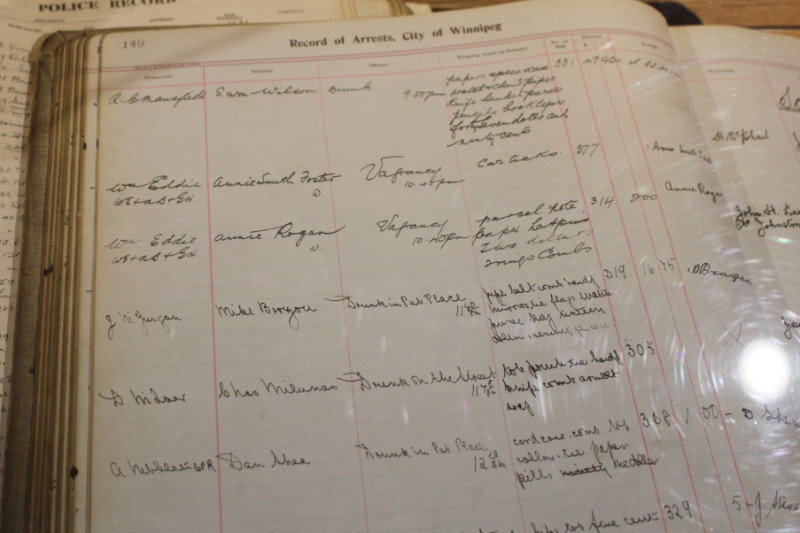

I’ve been spending time, off and on, organizing family history information left to me my mother (trees and books of memories compiled by other family members as well as her own notes), validating information, and filling in gaps. These days, much genealogy research can be done online without travelling to churches, archives, libraries, and government offices to pour over old records, many handwritten. The digitalization of these records, however, has its limits. In some records, not all information has been digitized. There is more to discover if you can read the original, often handwritten, source. Sometimes that image will be available online, sometimes you may need to send away for a copy.

Not everyone’s handwriting is the same. Some people write more legibly than others. These differences, compounded sometimes by a lack of understanding of context, has resulted in errors in the digitized records. I was puzzled by the presence of a child named Lily in my grandmother’s family. She showed up on the census index and in other people’s family trees. Her birth year was shown as the same year as my grandmother. There was no month identified. My grandmother was born in June. Unless my grandmother was a twin, it was unlikely she had a sibling born in the same year. As far as I knew, my grandmother was not a twin. It was only when I read the handwritten image of the 1906 census for myself that I understood what had happened. My grandmother’s name was Mathilda, but she was usually called Tillie (or Tilly). The T in the scrawled handwriting on that census had been transcribed as an L. In another situation, the K at the start of a surname had been transcribed as an E, making the record next to impossible to locate in a search.

There is more detective work involved in tracking down family information than simply being able to read handwriting. The original written information may be wrong, even when read correctly. For example, census takers wrote down information told to them. Sometimes they didn’t hear things correctly, guessed at spellings, or had difficulty dealing with language differences. When people wrote their own information, they didn’t necessarily record their names the same way or use the same spelling every time. Still, sorting all this out would be extremely difficult, if not impossible, if I couldn’t read cursive.

There are calls for cursive writing to be given more prominence in education. Being able to connect with the past is just one of the reasons cited. Other reasons include development of motor skills, reinforcement of learning, the potential for faster note taking because of increased writing speed caused by connecting letters and not lifting the pen off the page, and the stimulation of brain activity and creativity. Although I do most of my writing on the computer keyboard, I turn to cursive writing at times to get past a creative block, unlock new ideas, or allow a freer flow of words.

Personality comes through in cursive writing in a way that goes beyond use of language and turns of phrase. I can pick up an old letter and instantly recognize a great-aunt’s handwriting. I can picture my mother when I see her tiny, straight script on the page.

Language evolves over time. It is not unreasonable, therefore, to expect the way we represent it to change as well. Hieroglyphic writing may be beautiful to look at in ancient Egyptian monuments, but it would be very difficult to use this pictorial form as a written means of communication today. Hand and keyboard printing offer advantages over cursive. Letters are clearer and more consistent from person to person. The misinterpretations I’ve encountered in my family history research are less likely to occur. Anyone who’s struggled to read someone’s almost illegible handwriting (or perhaps even something they scrawled themselves) can appreciate the clarity of the printed and typed words. Still, I think it would be a shame to lose the ability to decipher the secrets of the past recorded with cursive writing.

If, fifty years down the road, my granddaughter should come across something I’d handwritten, will she need to hire an expert to decrypt it?

As to the words my great-uncle wrote to my father, here they are translated into English:

Become godly and grow tall, become the joy of your parents, and your now acquired destiny comfort you in all your sorrow. Let your baptism be the door, which will lead you to heaven.

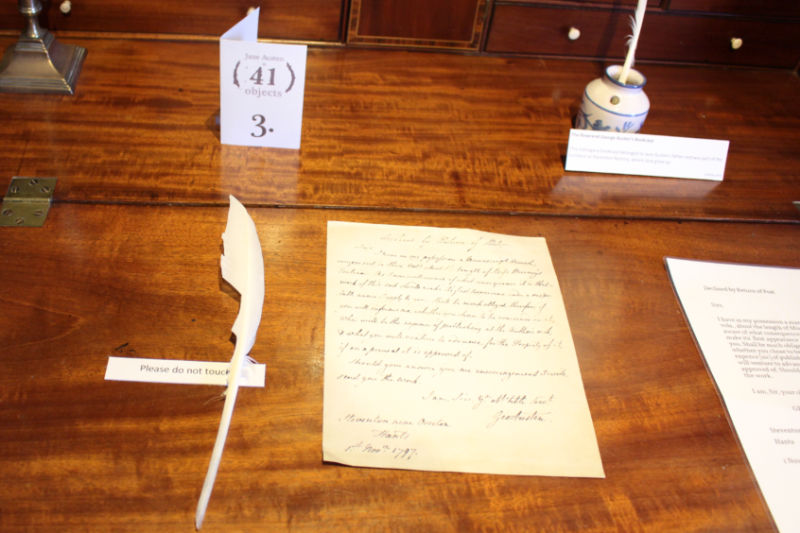

Note: the photo at the top of this post was taken at the Jane Austen House Museum in Chawton, Hampshire, England.

How very interesting! My grandfather’s last name was missing a letter when he emigrated to Canada. I often wonder how that happened.

Linda, sadly I think those kind of spelling errors were made with some frequency at immigration for a variety of reasons. I’m also discovering how common it is to find different spellings of the same names in different records.

Hi Donna. Interesting article. I strongly agree that official records from generations gone-by were often inaccurate due to language problems between the immigrants (newcomers) and the person behind the desk who either didn’t care, or didn’t have the resources/backup to do their jobs properly. It is most encouraging to see that in current days, there is often someone that assists government officials when a different language is required. And of course, the internet has opened us all up to the cultures of different nations, so we can double check things/records to ensure accuracy.

Doreen, I’m glad you found the article interesting. You can feel a bit like a detective trying to sort through inaccuracies in records caused by language differences and misunderstandings.

I really enjoyed the article & had some info I wanted to share with you but I would prefer to send it via your e-mail.Who were Albert’s God-parents.?Your grand-parents,Henry & Tillie Kletke were mine.

Hi Aunt Ruth, I’ve sent you an email. Glad you enjoyed the article.